Tips for IDing December bumblebees:

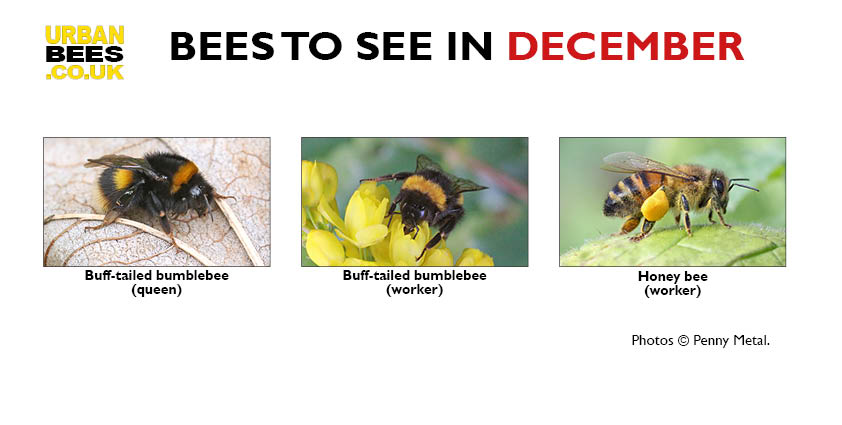

Bee identification suddenly got very easy as there are only two bee species flying at this time of year: buff-tailed bumblebees and honeybees, and in some areas it will only be the latter.

- Buff-tailed bumblebees (Bombus terrestris) – these fluffy, golden-striped bumblebees are the ones you’re most likely to see foraging between now and February, especially if you live in a city in the south of England. This winter activity was first recognised in the late 1990s when buff-tailed bumblebee workers (with the white tails) where observed in various sites. It’s believed that some summer queens set up nests in October (instead of hibernating until spring) and produced workers in November to take advantage of milder winters and the abundance of food provided by winter-flowering heathers, honeysuckles and especially widely-planted Mahonia, a tough shrub whose bright yellow flowers cheer up many an amenity shrubbery, car park, and city garden and park at this time of year and produce copious amounts of nectar and pollen. You’ll most likely see the white-tailed workers foraging on it and collecting blobs of its orange pollen in the baskets on their hind legs.

How to ID honey bees:

Western honey bees (Apis millefera) – the managed honeybee colony stays alive at this time of year by keeping warm in their hive and eating their honey which they spend all summer making and storing for their winter food. But on milder, sunny days or even cold, bright days when the sun has warmed up the hive, some worker bees will leave the colony to forage for winter-flowering shrubs near by, or just to go to the toilet (they don’t do this in the hive). That’s when you may see them. They are so much slimmer and smoother than bumblebees that there is no chance of confusing the two.

How to help bees in December:

- Plant a tree in your garden between now and February to feed bees in the future, or sponsor a street tree, or join a local tree planting group to plant trees in parks and community orchards. Some trees are better for bees than others, because they produce more nectar and pollen, or they supply it early in the spring, or in late autumn when little else is flowering. What we really need are trees that blossom sequentially producing a bee banquet throughout the year. Check our trees for bees guide. If you plant a Himalayan cherry (Prunus rufa) or a Tibetan cherry (Prunus serrula) you’ll not only have great blossom for bees in spring (as long as you plant single flowered varieties, not double-headed ones), but also fantastic rich coppery, peeling bark in the winter.

- Underplant your tree with Christmas rose (Helleborus niger) whose large, bowl-shaped flowers are borne in loose clusters in late winter and spring, and Elephant’s ears (Bergenia), Lungwort (Pulmonaria) to attract early flying bees next spring.

- Leave your garden unkept so as not to disturb bumblebee queens who may be hibernating in piles of old leaves, long grasses or under a shed.

- It’s not too late to undertake bee hotel winter maintenance. Follow our simple step by step guide to care for these solitary bees over winter. Watch out for other insects hibernating in any empty tubes. I found queen wasps and spiders!

- Offer a lethargic or exhausted buff-tailed bumblebee an emergency energy drink of sugary water. At this time of year they can get cold and exhausted very quickly after leaving the nest if they don’t quickly find nectar from a flower. A mixture of two tablespoons of white sugar to one tablespoon of water should revive them, but it may take them a while to find enough energy to suck up the liquid from the spoon or saucer you provide. Be patient. One way to ensure you are always prepared to revive a bee is by carrying a Bee Revival Kit with you at all times. You can buy these ingenious Bee Revival Kits – a vial filled with an ambrosia syrup that attaches to a key ring. An alternative is to pick a bee up and take her to a flowering bush, such as Mahonia, full of nectar-rich flowers if there is one nearby. But remember, bumblebees can sting if they feel threatened so pick her up on a leaf, or in a container. Never feed a bee honey. It sounds counterintuitive, but the bacterial spores of a disease that affects bee larvae can be found in honey and this brood disease is highly contagious.

.For information on IDing and helping bees at other times of the year see my Bees to See in November blog here Bees to See in October blog here, Bees to See in September blog here, Bees to See in August blog here, Bees to See in July blog here, Bees to See in June blog here, Bees to See in May blog here and Bees to See in April blog here, Bees to See in March blog here.